‘I have to ask my husband for literally everything’: How a warmer climate is changing gender roles

West Kameng, India — Dressed in a black sweatshirt and pink chugba – a traditional long gown – Tashi Lhamo, 53, cuts a striking figure. Sitting in her kitchen, smoke from the firewood billowing in her face, she tells CNN: “Now that’s all I do most of the time: cooking.”

Twenty years prior, Lhamo’s daily routine was very different. She spent her days tending to her yaks in the pastures atop the mountains of Arunachal Pradesh, the easternmost state of India. As she remembers the names of her favorite yaks (Karjamu, Pema, Dokpa…) Tashi nostalgically adds: “It was an entirely different life. It was freezing cold in the mountains. We would keep moving up the mountains with the yaks as summer set in and my routine wasn’t confined to any specific daily work as a woman (in the way) it is now.”

“I was my own boss. I could sell churpi [yak cheese] if I needed any money. Now I have to ask my husband for literally everything. It’s like yak calves asking their mothers for milk,” she says with a sigh.

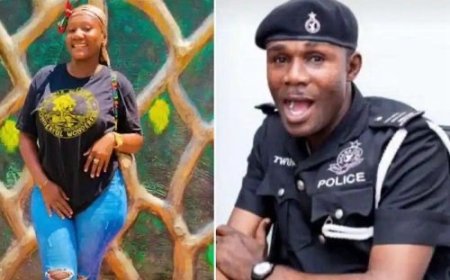

Tashi Lhamo, a former yak herder who is now a housewife, is pictured in her kitchen in Rama Camp, West Kameng, India.

Today, Tashi Lhamo is a homemaker, and her husband Tashi Phuntsu, 56, works various jobs. At time of writing, Phuntsu works on a local road construction project.

The Tashis belong to a semi-nomadic ethnic group known as the Brokpa and like so many other Bokpa, were once yak pastoralists. The couple owned over 200 yaks in their ancestral village, Lubrang. In those years, they would spend the summer months on the move, leading their yaks between mountain pastures. In the winter they would return to their village, their yaks grazing in nearby fields.

The Brokpa traditionally earn their livelihood by selling yak products: milk, cheese, fur and meat. They also farm in their villages. But over the past few decades, climate change has significantly affected Brokpa pastoralists, forcing many to give up yak rearing.

Over 20 years ago, Tashi Lhamo and Phuntsu were among the first yak herders in their community to transition into a sedentary lifestyle by settling in Rama Camp, a farming village tucked away in a picturesque valley at the foothills of Lubrang. “We moved down here because it was becoming increasingly difficult to keep yak. We decided to try our luck here,” they tell CNN.

But moving down from the mountains has also meant that for Lhamo, and other Brokpa women, they’ve also moved down the social hierarchy, simply by virtue of being women. As the world continues to warm, making yak herding untenable, Tashi Lhamo’s life is a cautionary tale of what awaits women in the dwindling herding communities.

Worsening environmental conditions threatens the way of life for thousands

Yak is a high-altitude, cold weather bovine but a changing climate is threatening the survival of this species.

“We have observed a general decline in fodder over the years, including paisang leaves, yak’s favorite winter food,” says Tseng Dorji, a former yak herder and field coordinator with the Indian Council for Agricultural Research-National Research Centre for Yak (ICAR-NRCY), India’s premier yak research institute. “We suspect this is due to rise in temperatures and increasingly erratic weather patterns,” he tells CNN.

Temperatures are rising in the Indian Himalayan region where yaks are reared. The situation is even more acute in the eastern Himalayas, where Arunachal Pradesh is situated, with records of higher temperatures in the eastern than in the western Himalayan region.

During the winter period, yaks in Lubrang graze in fields near the village. As summer approaches, herders migrate to pastures located in higher altitudes, as yaks can't weather the summer heat in the village.

According to government data from 2022, Arunachal Pradesh, a “highly vulnerable” region and one of the eight most vulnerable Indian states to climate change, has witnessed a temperature increase of 0.59 degrees Celsius in the short span of the last four decades. This remote mountainous state has also recorded erratic climatic events such as drying up of mountain springs in recent years.

Climate scientists say the extreme heat waves that killed people, livestock and crops in July 2023 would have been “virtually impossible” without climate change – and that change is of around 1.2 degrees Celsius more than in the pre-industrial period. A 2021 study reported an increase of temperature by 1.5 degrees Celsius in the Indian Himalayas in the last century.

Despite efforts by the ICAR-NRCY to develop heat-resistant yak hybrids, the worsening environmental challenges faced by the Brokpa have resulted in a decrease in the number of yak herders. Tseng of ICAR-NRCY, himself a Brokpa, says: “The number of yak herders have dwindled to about 1,800 – from approximately 3,000 – in two decades.”

An Arunachali yak in the Brokpa village of Lubrang, India. Yaks have been the economic mainstay of the Brokpa semi-nomadic community of Arunachal Pradesh for thousands of years, until climate change began to impact yak rearing.

Rinchin Lama, the deputy director of Arunachal Pradesh’s department of animal husbandry, veterinary and dairy development, corroborates this, saying: “While there are 644 yak herder families in Arunachal Pradesh as per our survey records, the actual number of people currently engaged in rearing and herding yaks would be around 1800.”

The obvious impact of this transition is changes to the Bokpa way of life, with former yak herders making ends meet as petty traders, day-wage laborers on the many mountainous roads in need of regular maintenance, or subsistence farmers, who mostly grow vegetables or grains for their own consumption but sell any surplus in local markets. But the more insidious impact has been a significant shift in gender dynamics, resulting in Brokpa women’s loss of power and influence. Forced to integrate other communities in order to survive, Bokpa women are losing the relative equality they enjoyed in their’s.

Losing influence

In Brokpa pastoralist settlements, local administration is carried out by the tsorgan, the village chief, supported by the village council known as mangma. While the tsorgan is usually an elderly male, every adult, irrespective of gender, is a member of the mangma.

“In mangma councils, Brokpa women participate actively although they rarely make it to the leadership,” says Yeshe Dorje Thongchi, a prominent Indigenous writer from West Kameng who wrote an acclaimed novel, Sonam, that depicted the lives of yak herders. “The situation is far from ideal for women, but they do influence decisions to some extent.”

But society is organized differently when you come down from the mountain. The agricultural community former yak herders like the Tashis have integrated is called the Ungpa. The Ungpa – and agriculturists communities more broadly – traditionally favor men over women, with decision-making and political arenas heavily dominated by men. In Arunachal Pradesh – where the majority of people are agriculturists – there are only 5 women legislators out of a total 60 in the state assembly, just 8.3%. This gender disparity in local politics is all the more striking given that the state has more women voters to men (422,418 to 409,200).

Aside from the loss of decision-making power, Brokpa women, like Lhamo, who have settled among the Ungpa have also lost most of their economic independence and the power they traditionally wielded through a marriage institution known as khor dekpa.

Khor depka is a system of fraternal polyandry, a form of marriage where a woman may marry two or more brothers. Such marriages can be proposed by any of the partners and require the consent of all involved.

Fraternal polyandry is practiced by pastoralists in Tibet and the Himalayas. “The partners in such marriages look after the animals and the homestead without strict division of labor,” explains Lhamo, several of whose relatives were in khor dekpa alliances. Lhamo’s husband, Phuntsu, had no brothers.

Describing to CNN what the roles within the household would be, Lhamo says: “One brother-husband moves with the animals, another looks after the homestead, and the wife goes down to the lowland villages to sell yak products. They may juggle between these roles.”

A Brokpa herder milks one of his yaks in Lubrang.

Similarly, access to the family’s resources is not as strictly gendered. As Lhamo tells CNN, a woman can sell any of the family’s yak products at will if she needs money. This is confirmed by Li Zhi-nong, a research fellow at the Centre for Studies of Ethnic Minorities in China’s Yunnan University who’s been studying polyandry and family dynamics in the Himalayan societies for over a decade. Li adds: “Both women and men prefer fraternal polyandry because it adds more labor force to the family and ensures better economic conditions. In the mountains, pastures and productive lands are scarce and this form of marriage prevents subdivision of pastures, arable lands and animal herds. It also limits the number of children born in a family.”

But Lhamo says that as with other parts of Brokpa culture that are changing, khor dekpa marriages are in decline. To explain why, Li at Yunnan University says: “These sorts of marital alliances are a means to ensure economic stability and quality of life in the resource-scarce harsh geography of the high Himalayas.”

In other words, as Tashi Lhamo puts it: “If you’re not living in the mountains and not moving with yaks, it doesn’t make sense.”

‘I was expected to allow my name to be used but the rest of the business to be run by my husband’

In 1976, India passed the Equal Remuneration Act which stated that men and women doing the same work should earn the same wage, and penalized discrimination against female employees. Yet in the farming communities former yak herders have settled in, many Brokpa women find themselves working odd jobs for a lesser wage than their male co-workers.

Sitting in her kitchen, Tashi Lhamo tells CNN: “It’s hard for a woman to find a job that’s worth doing. Here many don’t even want to employ women.” Lhamo, like most women in Ungpa communities, keeps a kitchen garden which provides vegetables for the family but doesn’t earn her an income.

When Lhamo and her husband first moved down the mountain, she took work as a road construction laborer, but she says she was paid little over half of what the men made. With little else to do outside the household, Lhamo became largely dependent on her husband’s income.“That [was] something new and strange for me,” she says. “In the brok [Brokpa settlements], we didn’t have this idea that women can’t do equal work with men.”

A Brokpa settlement is set amid the grazing fields in Lubrang.

Lhamo then tried to participate in local governance, as she would have done in the Brokpa’s mangma councils. In 2013 she was elected to the panchayat, the decision-making authority at the village level in India, in one of the seats reserved for women by law. Yet as the mother of three tells CNN, in the village she now called home, there was no expectation that she would play an active role in deciding how anything was run.

“All that was expected of me was that I allow my name to be used and the rest of the business be run by my husband,” she says. “I didn’t agree to that and attended all the meetings. But for all the other women panchayat members, it was mostly their husbands who called the shots. The attitude is that women aren’t meant to be politicians or decision makers — that’s men’s business.”

It has been extensively reported in both Indian media and academic texts that quotas introduced to increase women’s political participation have done little to shift power to women, with women said to be acting as proxies for men, as Lhamo’s own experiences attest.

Lhamo’s term on the panchayat ended in 2018 and she didn’t run for another because she felt that there was little she could really do. “Whenever there was an important decision to be made, I was asked to take advice from the elderly men of the village and represent their opinion,” she says. “In the brok, I didn’t see any woman becoming a tsorgan (chief), but we still raised our voice in the mangma meetings and we were taken seriously.”

When asked what change would look like, Tashi Lhamo says with a sense of resignation as the firewood burns out and she shifts to cleaning the kitchen: “I don’t know when we can change the deep gender disparities here,” before adding wistfully: “The ideal scenario for Brokpa women is to be able to remain in the pastoral life. Of course, with more formal recognition of their leadership potential.”

But if it is hard to change the expectation that a woman’s place is in the home and not in local politics or in the workforce, with temperatures projected to continue to rise, it is just as hard to change the warming climate that forced Tashi Lhamo along with her family and thousands of others who’ve abandoned western Arunachal Pradesh’s imposing mountains and given up the way of life that has existed for thousands of years.

Despite how tough life could be in the mountains, and in spite of the decades that have passed, Tashi Lhamo still pines for a life of yak rearing and what that way of life enabled her to do. If she had the money, she tells CNN: “I’d choose the freedom of the mountains right away.”

Source: CNN