The Priest, the Power Broker and the Pop Star

Just a few days after Mayor Eric Adams was indicted on corruption charges, the pop star Sabrina Carpenter stood onstage at Madison Square Garden and said something startling into her glittery microphone: “Should we talk about how I got the mayor indicted?”

Ms. Carpenter’s quip was both tantalizing and quite obviously false: The singer played no role in the investigation and prosecution of Mr. Adams.

But her offhand remark in front of 20,000 fans in September did pull back the curtain, ever so slightly, on a bizarre side plot in the Adams affair — a story whose contours sound almost like the beginning of a joke: Did you hear the one about the pop star, the politician and the priest?

The priest is Msgr. Jamie J. Gigantiello, a pastor who has led three Brooklyn parishes over his 30-year career and has known Mr. Adams, the former Brooklyn borough president, for decades. The priest also is a pastor to, and close friend of, Frank Carone, the mayor’s former chief of staff.

Now the monsignor is at the center of an unholy brawl. The fight has reached the highest levels of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn and the offices of federal prosecutors in the Eastern District of New York, who have subpoenaed records from transactions worth nearly $2 million between the monsignor’s parish and businesses connected to Mr. Carone.

The nature of the federal investigation — or who its target might be — is not publicly known. Nobody has been charged with a crime, and it is unclear whether the priest or Mr. Carone did anything improper or illegal.

Monsignor Gigantiello had already been demoted over his decision to allow Ms. Carpenter to film a risqué music video on the altar of a church in his parish for $5,000.

But this week, Robert J. Brennan, the bishop of Brooklyn, took the unusual step of issuing to local reporters a blistering condemnation of the priest.

The bishop announced that he was relieving “Monsignor Jamie Gigantiello, the current pastor, of any pastoral oversight or governance role at the parish,” and portrayed him as a renegade priest who had made backroom financial deals without proper documentation and used a parish credit card to buy personal items.

The monsignor disputes the accusations — the deals with Mr. Carone were made to benefit the parish, he said, and the personal spending on the parish credit card was not inappropriate.

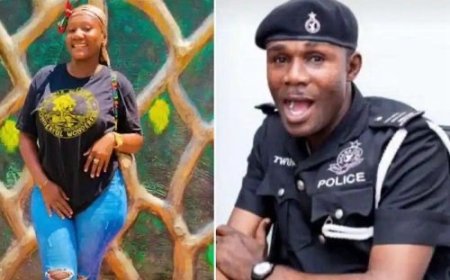

Credit...Gabriele Holtermann/SIPA USA, via Associated Press

Critics of Monsignor Gigantiello say he promotes himself in the press and has imperiled his parish by making unusual investments.

But among the parishioners at his Williamsburg churches, Our Lady of Mount Carmel and Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, where he is known as Monsignor Jamie, he is beloved.

Many of his congregants see Monsignor Gigantiello, 65, as a charismatic and effective spiritual leader who leads energetic and community-oriented Masses, renovates church buildings and reliably shows up in difficult times.

They say he has been unfairly treated by Bishop Brennan, who publicly humiliated him over the music video fiasco, stripped him of authority at his parish and sidelined him from his successful fund-raising efforts.

To some parishioners, the punishment feels vindictive. “Monsignor Jamie is being targeted, and our community has been targeted by the Brooklyn diocese,” said Dr. Joseph Ciuffo, who worships at Monsignor Gigantiello’s parish. “It’s a slur campaign.”

“It’s very dramatic to say,” said Msgr. David L. Cassato, a fellow priest and close friend of Monsignor Gigantiello’s, “but it’s like a crucifixion.”

A Music Video, and a Cleansing Mass

The story of the monsignor’s troubles is actually two stories. The first concerns Ms. Carpenter, the singer of “Espresso” and “Please Please Please.”

The request wasn’t unique. Monsignor Gigantiello had approved similar filming proposals in the past from “Blue Bloods,” the CBS police drama, and “The Irishman,” a gangster movie directed by Martin Scorsese. He saw them as an opportunity to make some money for the churches. He said he had spent about $2.5 million to renovate Annunciation, including about $325,000 for its massive pipe organ.

When approached by Ms. Carpenter’s representatives, he glanced at the script for the video and agreed to a daylong rental for $5,000. But he did not supervise the production, which included covering the altar in candles and pastel-colored coffins. One close-up showed a coffin inscribed with an epithet that had not appeared in the script: “RIP Bitch.”

In the video, the singer, wearing a minuscule black dress and mourner’s veil, shimmies up to the coffins suggestively. The viewer presumes that inside are some of the men who earlier in the video made eyes at Ms. Carpenter before dying violent deaths. The singer hits her high notes wearing the spatter of their blood on her face.

The video was released on Halloween in 2023. The next day, Monsignor Gigantiello received a phone call from Bishop Brennan.

“He said he was very upset about the video,” Monsignor Gigantiello said in an interview. He then watched it for himself — and quickly understood that he had erred in allowing the church to be used.

The next day, he said, he met with Bishop Brennan and apologized. The bishop told him that he was immediately removing him from his role as the diocese’s vicar for development and taking away his administrative oversight of the parish.

In a statement released at the time, Bishop Brennan said he was “appalled at what was filmed at Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary Church in Brooklyn.” He personally led a cleansing Mass of Reparation at the church.

Nearly a year later, performing at a sold-out concert at Madison Square Garden, Ms. Carpenter made her remark about the mayor’s legal woes, which spread across social media and brought the video scandal back into tabloid headlines.

Through a spokeswoman, Ms. Carpenter declined to comment.

‘Hold On to Your Wallet’

For a religious leader, Monsignor Gigantiello has been uncommonly entrepreneurial. Long before entering the priesthood, he studied at the Culinary Institute of America; now he is the host of a cooking show called “Breaking Bread,” the author of a cookbook by the same name and the purveyor of “A Taste of Heaven,” a tomato sauce.

He has also made considerable money as an investor — including in the New York real estate market — before and even after he was ordained.

In 1980, he bought a home in Brooklyn for himself, his sister and his mother to live in. He paid $50,000 and about a decade later sold it for about $225,000. He later bought his mother her own apartment and inherited a windfall profit after she died.

He continued to buy low and sell high. With his friend Monsignor Cassato, he bought and later sold a house in Quogue, on Long Island, netting nearly $400,000. Together they bought a condominium in Pompano Beach, Fla., and a house in Westhampton Beach, N.Y., with four bedrooms and a poolside kitchen. They bought the house for $850,000 and listed it for sale this summer for $2.5 million. Monsignor Gigantiello also owns a quarter of a timeshare in St. Maarten (the remaining shares are owned by three other priests).

He knows that his real estate portfolio may raise eyebrows. “As priests,” he said, “we do not take the vow of poverty. We’re not religious order priests, and so we’re allowed to own our own things.”

Knowing how to generate revenue can be a valuable skill in the church, Monsignor Gigantiello explained, especially in an era when dioceses are hobbled by financial settlements owed to victims of abuse.

Over his three decades as a priest, Monsignor Gigantiello said, he has raised money for renovations and landscaping at parish buildings, increased attendance at Mass and left his parishes financially solvent.

In 2008, he was named vicar for development at the Brooklyn diocese, responsible for fund-raising. He frequently brought in $2 million in a single night for a program that pays tuition for underprivileged children to attend Catholic schools, said Angelo Vivolo, an entrepreneur, City University of New York trustee and philanthropist who supports Italian American and Catholic causes.

During his years as vicar, the priest raised $105 million in a capital campaign for the diocese — $25 million more than the goal amount, said Nicholas DiMarzio, the former bishop of Brooklyn.

His fund-raising acumen is well known even beyond the diocese. At a Fat Tuesday celebration a few years ago held at Tiro a Segno, a private Italian heritage club in Manhattan, Dr. Ciuffo introduced himself to Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan, the archbishop of New York, telling him that he was a parishioner of Monsignor Gigantiello’s.

“Oh, that Monsignor Jamie,” Dr. Ciuffo said the archbishop said to him in a jovial tone. “Better hold on to your wallet!”

Mr. Vivolo said that given Monsignor Gigantiello’s talents, Bishop Brennan’s punishment “is too much.”

“How do you take a guy who annually raises millions for the diocesan schools, and tell him he is not allowed to fund-raise for the church?” he said. “It’s like cutting your nose to spite your face.”

A Fateful Friendship

Monsignor Gigantiello’s brief connection to Sabrina Carpenter may have been the start of his troubles. His long relationship with Mr. Carone compounded the situation.

In 2008, long before Mr. Carone went to work for Mr. Adams, Monsignor Gigantiello reached out to him as part of his fund-raising efforts for the church. Mr. Carone, a lawyer, entrepreneur and investor, helped set up dinners at the rectory where the priest could get to know other business leaders in the community.

The monsignor and Mr. Carone were entwined in a particularly Brooklyn-Italian-American-Catholic way: Mr. Carone’s mother had known Monsignor Cassato since they were in grade school together at a neighborhood Catholic school. When Mr. Carone’s father died, Monsignor Cassato brought with him to the wake a priest he was mentoring: Jamie Gigantiello.

From there, Mr. Carone and Monsignor Gigantiello grew to be close friends. “Monsignor Jamie has a unique way of bringing our Catholic community together through our faith, unlike anyone I have ever experienced,” Mr. Carone said in a statement.

Over the years, the priest sought Mr. Carone’s help investing the profits he generated from real estate.

In 2018, Monsignor Gigantiello said, he turned to Mr. Carone for help investing the parish’s money, too. The diocese had given a condo developer a long-term lease on church property across the street from Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary — a deal in which the developer initially paid the parish $1 million.

The monsignor said he asked Mr. Carone to invest the money on the parish’s behalf. He did not ask for specifics about the investment. “He was a dear friend that I trusted,” he said.

By 2021, Mr. Carone’s firm had repaid the parish’s $1 million, along with a return of about $120,000.

Monsignor Gigantiello said he then asked Mr. Carone to invest another $900,000 on behalf of the parish. Soon after, the priest received a call from a reporter for The New York Daily News, who told him that a law enforcement agency was investigating Mr. Carone’s investments.

The priest called his friend and got the $900,000 back, several months later, without interest. “I did not want the church to be caught up in any investigations,” he said.

A spokesman for the diocese said that the monsignor had violated rules by not seeking approval for “commitment of parish resources” greater than $30,000.

The spokesman said that the priest had not secured proper paperwork that would show what Mr. Carone planned to do with the $1 million, nor did he have sufficient documentation for the subsequent deal. The documentation that the diocese did find for one transaction showed only that a company associated with Mr. Carone had pledged to repay the parish’s money with interest — an arrangement the diocese sees as an apparent loan.

In a statement, Mr. Carone denied that the transaction was a loan, and said he had never needed or taken a loan from a church. He said he had invested the parish’s money, but declined to elaborate.

“In light of disagreements between the monsignor and the current leadership at the diocese,” Mr. Carone said, “I’m not going to comment on his or other investments.”

He also declined to address the Eastern District investigation that led to the subpoena.

Fast forward to 2023: Federal agents raided the home of Mr. Adams’s chief campaign fund-raiser as part of an investigation overseen by Damian Williams, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, into the activities of the mayor and his associates.

Less than a year later, Mr. Adams was indicted on five criminal charges, including bribery. A half-dozen senior aides, including the police commissioner and the head of the school system, resigned amid several other investigations.

Tracking Charges and Investigations in Eric Adams’s Orbit

Five corruption inquiries have reached into the world of Mayor Eric Adams of New York. Here is a closer look at the charges against Mr. Adams and how people with ties to him are related to the inquiries.

A few months before the mayor was charged in Manhattan, a different U.S. attorney — Breon S. Peace, of the Eastern District of New York, which includes Brooklyn — had subpoenaed records from Monsignor Gigantiello’s parish related to its financial dealings with Mr. Carone.

The Brooklyn inquiry involving Mr. Carone and the church is distinct from the investigation that led to the mayor’s indictment, and from the others involving his aides. But in a city that has been captivated by the baffling depth and breadth of the mayor’s entanglements, it has drawn unwelcome attention to the parish.

Monsignor Gigantiello has complied with the subpoena, his lawyer, Arthur L. Aidala, said, turning over to investigators the diocese’s audit of the parish conducted after the Sabrina Carpenter drama.

Mr. Carone, who no longer works at City Hall but remains a top adviser to the mayor, has not been charged with any wrongdoing. The priest’s lawyer said that the prosecutor overseeing the investigation had told him that Monsignor Gigantiello is not a target of the investigation.

A spokesman for the U.S. attorney’s office declined to comment.

The diocese also noted that in its own continued investigation, it had found that Monsignor Gigantiello had used a church credit card for “substantial personal expenses.”

A spokesman for the diocese added that its investigators had found that the monsignor charged over $600,000 to his parish credit card from 2017 through 2023, and that he had told investigators that nearly $120,000 went toward personal expenses.

“There is no evidence that Monsignor Gigantiello’s use of his parish credit card for furniture for his Florida vacation property, airfare and personal clothing was an authorized form of compensation from the diocese,” the spokesman said.

Monsignor Gigantiello said most of the charges on the card — $480,000 — were not for personal expenses. He noted that the charges over seven years amounted to less than $6,000 per month, which he said was used to run two churches and pay for renovations, upkeep and parish events.

As for the remaining $120,000, he said, Bishop DiMarzio, his previous boss, had approved an annual additional salary for extra work he was undertaking for the diocese. Monsignor Gigantiello said the amount was $30,000 per year and it was sent to him through the parish. His lawyer, Mr. Aidala, said the monsignor had paid taxes on all of his income.

In an interview, Bishop DiMarzio confirmed that when Monsignor Gigantiello took on additional responsibility as vicar for development, Bishop DiMarzio requested that the board consider awarding the monsignor additional compensation.

The bishop said he was not certain of the amount that was decided upon. But the money “was sent to the parish, and in hindsight, it should have been sent to him directly,” he said. “It was earmarked for his personal use.”

Bishop DiMarzio said this week that no one involved in the diocese’s investigation of Monsignor Gigantiello had reached out to him to ask about the monsignor’s compensation.

“He is a hard worker and a very good priest,” Bishop DiMarzio said. “I never had a problem with him in 18 years. There clearly is a conflict between personalities now.”

In the last two weeks, that conflict has created yet another strange subplot: An administrator sent by Bishop Brennan to oversee Monsignor Gigantiello’s parish was removed from his post after the monsignor and others accused him of using terms like “Goombah” and “the Mob” to describe Italians.

After the monsignor turned over rectory surveillance video of the man uttering the slurs, the bishop removed the administrator — but castigated the monsignor for recording private conversations. Now, lawyers are duking it out over whether the slurs or the surreptitious recordings were the greater sin.

Leaving His Mark

On a recent Sunday at Our Lady of Mount Carmel, there was standing room only as Monsignor Gigantiello conducted Mass in elaborate green and white vestments.

His service began with a procession of children, and then a congregant delivered a reading in Italian. Before the communion sacrament, loved ones of those who had died this year were invited to the altar to light candles. Monsignor Gigantiello added some levity by leading the congregation in singing “Happy Birthday” to those who had birthdays that week.

Before the service concluded, there were announcements, including from a member of the parish council. He made reference to the tension with the bishop and the diocese. “We’re not going to stand around and let anyone — I don’t care who — push us around,” the councilman said. “We support our church and we support our pastor.” Much of the congregation began to applaud.

The monsignor said the entire drama had left him shaken and unsure of who to trust. “It’s sad when the D.O.J. treats you better and with more respect than your own bishop,” he said.

Whatever happens next, he has left his stamp on the parish. On a wall in a rec room at Our Lady of Mount Carmel is a mural he commissioned. It shows Monsignor Gigantiello standing above a group of parishioners, reaching up toward the heavens.

Source: New York Times