The Eni-Vitol – Ghana Arbitration: A total embarrassment!

The Attorney General of Ghana is trying desperately to spin serious embarrassment to the Republic of Ghana in an international tribunal using all the tools in his propaganda toolkit.

On 16th August 2021, two investors in Ghana’s petroleum sector, Eni (an Italian multinational) and Vitol (a Swiss multinational) filed notice under the UNCITRAL rules of its intention to pursue international arbitration in response to directives issued to it by the government of Ghana that it felt breached its petroleum agreement with the country. Eni-Vitol had come to the conclusion that the political context in which these directives were issued made it impossible for it to obtain fair hearing and justice in the domestic jurisdiction.

The origin of the controversy

The government of Ghana had ordered it to merge its oil field, which had been successfully producing oil for a number of years, after investments exceeding $6 billion, with an oil block next door that has never produced oil and seen in total roughly $100 million of investments.

Furthermore, the government wanted Eni-Vitol to also hand over roughly 55% of the combined entity to the owner of the said oil block next door. Ghana’s domestic laws allow the government to do this. However, petroleum exploration and production constitute an international domain in which certain global business and technical logics operate and have operated for many decades.

Whilst the Ghanaian courts have been focused purely on what the law allowed the government to do, and were inclined to rely on the curious technical testimony of the country’s national oil company (GNPC), the truth of the matter is that there are international standards in these matters and any investor coming into any country to invest billions of dollars will ensure that they also have the protection of international law and technical regimes. Given the sheer amount of money they stood to lose (reckoned in billions of dollars), it came as no surprise when Eni-Vitol decided to take their case internationally.

We have discussed the issues at length elsewhere

In a previous essay on this site, I have chronicled carefully the history of the controversy in significant detail. In another essay I laid out the basis of my argument that GNPC’s technical testimony in this instance was procured by political pressure as it simply didn’t hold water.

As the reader would no doubt notice from these essays, civil society organisations (CSOs) in Ghana engaged in the petroleum sector, especially IMANI and ACEP, have exhaustively examined the matters in the controversy and, with deep patriotic concern, warned the government that its actions in the attempted forced “unitisation” of the two offshore petroleum sites are completely against the national interest. In this short essay, we shall show why the tribunal’s final decision given this week, and the consequences of the unjustified “forced unitisation” directives, are all highly embarrassing for Ghana and completely detrimental to the country’s reputation and economic position.

The case against the government of Ghana

When Eni-Vitol filed its arbitration notice, the government of Ghana initially didn’t even bother to submit a detailed response.

Eni-Vitol nonetheless proceeded to present their joint statement of claim. At the heart of their case is the simple fact that Ghana is trying to force them to merge a highly valuable, and proven, oil field with another one that has not yet been properly assessed, to international standards, in order to determine if there is even any oil in place.

In the circumstances, such an attempt amounts to a pure ruse to seize a large part of a highly lucrative asset and hand it over to another business without any sensible foundation. International law frowns on unjust expropriation of foreign-owned assets under different guises.

If the government was genuinely interested in merging the fields purely because it wishes to improve efficiency, it would first focus on ensuring that the other business owning the “greenfield” block undertakes the proper technical investigations to confirm if indeed there is oil on that block, and what quantity exactly. This is at the heart of the whole matter.

In fact, carefully analysed from that perspective, Ghana itself STOOD TO LOSE if a merger was forced between a lucrative and fertile oil block and a potentially infertile and valueless one since the merger will affect Ghana’s own holdings in both blocks, which were not uniform at the time of the proposed merger.

In my earlier essay, referenced above, I lay out the various scenarios in which both Eni-Vitol and Ghana would lose massive amounts of money if the unitisation proceeded. The only beneficiary would have been the owner of the block next door, the optimistically named “Afina field”. The question that has never been properly addressed is why the government of Ghana was willing to go to such lengths to benefit the Afina owners, even to the detriment of its own economic position and international reputation.

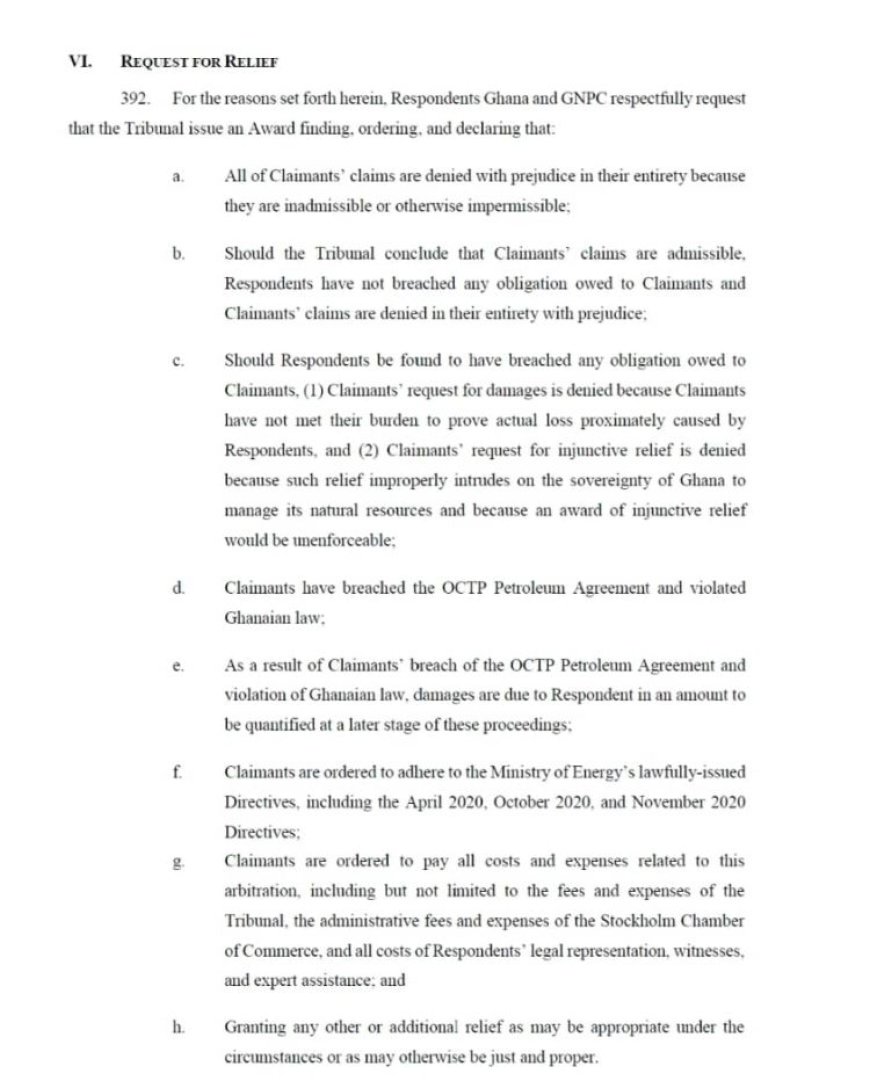

In light of its position on the matter, what specifically did Eni-Vitol want the international tribunal to do for them? Below are the reliefs they were seeking, produced in full.

A careful reading of the reliefs should show that the bulk of Eni-Vitol’s expectations are in the nature of a declaration that the government’s directives for forced unitisation are unlawful and unjustifiable and should not proceed in the manner the government had sought to bring them about. That really is it.

The tribunal, even per the Attorney General’s own atrociously uncandid summary, has declared the government of Ghana’s attempt and approach at forced unitisation to be in breach of its petroleum agreement with Eni-Vitol and therefore unlawful and unjustified. Simple!

The government’s attempt at defending its actions

What was the government’s principal defense at the tribunal and how does it square with how the Attorney General is attempting to spin the outcomes of the proceedings?

The government’s super-expensive international lawyers summed up its case in the paragraph below found in the opening of its statement of defense. (“Claimants” in the text extract refers to Eni-Vitol.)

Government of Ghana’s primary aim in paying for these expensive lawyers to fight its baseless cause at arbitration was to get the tribunal to agree with its approach to the forced unitisation.

The government knew that its case was not in the national interest

The Ghanaian government did not only want the tribunal to agree with its inherently disordered and self-detrimental approach to the merger, which would have damaged the interests of its own citizens, they also wanted the tribunal to find the investors guilty of breaching their agreement with Ghana by not lying down and rolling over immediately they were asked to hand over a juicy chunk of their asset to another business.

The true mindset of the government’s agents in this matter, especially the Attorney General who instructed these lawyers, is exposed by paragraph 49 of the government’s statement of defense.

What that paragraph simply says is that in the end even if the merger leads to losses, Ghana is the ultimate bearer of those losses and so why is Eni-Vitol sweating? Such a deeply unpatriotic and reckless argument to make!

The government, egged on by the Attorney General, believes that it can proceed with technically reckless actions in Ghana’s petroleum sector, actions that will impose losses on the citizens of the country, with no consequence at all. What it is essentially saying here to investors is that, “why are you crying more than the bereaved? We are willing to bear the losses.”

In fact, the government spends the overwhelming proportion of its defense arguing against “commerciality” as an important logic in any regulatory directive that affects the economic structure of a petroleum transaction in which Ghana is involved. It attempts, in breathtaking elaborateness, to make the case that even if the Afina block does not have any oil, it is fine to merge it with the oil producing Sankofa – Gye Nyame field (the one in which Eni-Vitol have majority interest) even though the inevitable result will be the dilution of economic returns for both Ghana and Eni-Vitol, and even if the only one who stands to benefit is the third-party private business next door.

The disorganised logic of the government’s case

Perhaps, in a belated recognition that their longwinded arguments making the case that commercial logic is irrelevant and all that matters is the discretion of government ministers, the government’s expensive lawyers began to moderate their tone somewhat when it came to defending the decision of the government to award 54.5% of the merged field to the private owner of the next-door Afina block.

What they are saying here, in essence, is that the precise allocation of acreage in the combined block is still in the works. The illogicality of that argument is inherent in fact that any such decision has to be based on knowledge of how much oil is in the separate blocks. Without knowing how much oil each party is in essence “bringing to the combined table”, there is no technically sound way to divvy up the combined block. Since determining “commerciality” is how you confirm that the owner of the non-producing oil block is bringing anything to the table at all, the hollowness of this belated concession about the exact split of the combined field becomes crystal clear, laid side by side with the claim that commerciality is an irrelevant factor.

After all this turning and twisting, how did the government want the tribunal to rule? Ghana’s counter-claims offer a good view.

Ghana wanted the tribunal to punish Eni-Vitol

The government also wanted damages. Yes, it wanted to be paid by the investors for the pleasure of being robbed of their petroleum assets.

After these brazen demands, the government proceeded to list its requested reliefs.

The government failed to secure any of its principal reliefs

The judges at the tribunal must have had a good laugh. But deep down they were not amused. The government’s punitive claims against Eni-Vitol were totally dismissed. By even the twisted accounts of the Attorney General, it is clear that the tribunal did not so much look at them twice.

Whilst the Attorney General is celebrating the decision of the tribunal not to award large damages against Ghana, and its instructions for Ghana to only pay half of the arbitration costs, the truth is that the government’s attempt to get the tribunal to sympathise with its positions was wholly unsuccessful. Eni-Vitol on the other hand got what they mostly set out to achieve: a ruling by an international tribunal that the government’s conduct is unlawful, on the basis of international standards and a more expansive reading of the country’s own laws.

The tribunal ruled in Ghana’s interest

In the end, though, especially for us in civil society, what matters is that the citizens understand clearly that the international tribunal was on their side and their government was acting in ways that would have considerably damaged their interests.

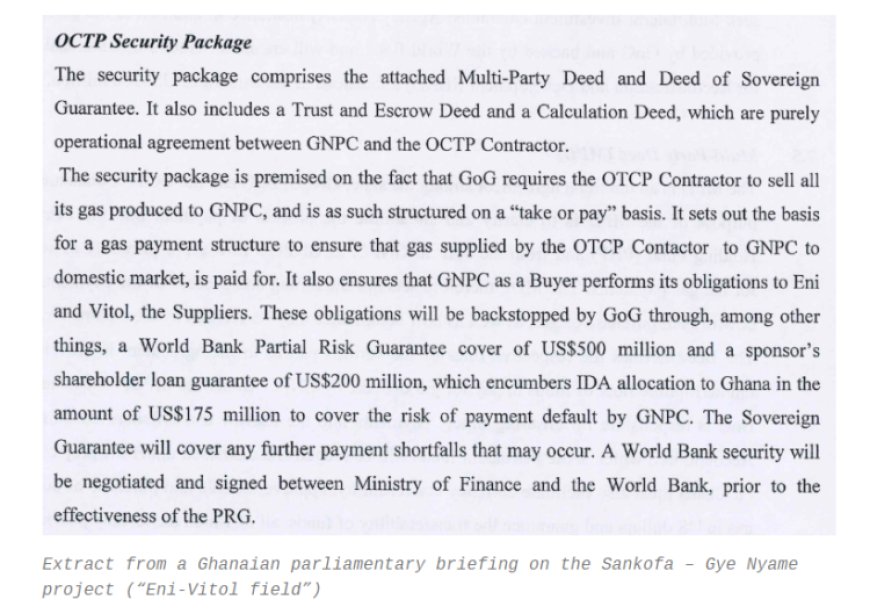

Ghana had to issue sovereign guarantees and tap the World Bank’s guarantee facility in order to get the Eni-Vitol field operational.

Extract from a Ghanaian parliamentary briefing on the Sankofa – Gye Nyame project (“Eni-Vitol field”)

The Eni-Vitol field is now the major supplier of gas for the country’s power plants. Ghana obtains significant revenues from its equity stake in the field. Forcing this lucrative project into a poorly thought through merger with an unproven, greenfield, block would have caused massive disruption, undermined the commercial viability of the whole enterprise, and therefore ultimately eroded the benefits of the producing and proven asset to the people of Ghana. It is very likely that the Eni-Vitol would have stopped gas production and plunged Ghana into dumsor should the situation had persisted down the path it was on.

Ghana has already suffered because of the government’s actions

Already, the needless controversy over the forced unitisation has cost Ghana dearly. The development of major oil discoveries such as Eban and Akoma have stalled. There is evidence that some major international oil companies have been looking askance at the country since the government began this ill-fated expropriation agenda. Ghana hasn’t brought a new oil field onstream for years (Jubilee South-East doesn’t really count as it is merely the extension of an existing field). Oil output and state revenues from petroleum have been declining steadily and steeply.

Someone must be held accountable

The Attorney General’s conduct in failing to properly advise the country, in promoting a baseless position in an international forum, in opting to engage hyper-expensive lawyers costing this country millions of dollars, and in the end failing to secure any of the principal reliefs sought by Ghana is atrociously bad on its own. Seeking to spin such a disastrous outcome as a victory is simply disreputable and ought not to pass without strong words from civil society and the citizenry.

As a starting point, citizens and civil society activists should demand complete transparency in respect of all monies paid to the likes of Foley Hoag.

We are also hearing that White & Case, which partners a politically exposed local law firm, had a role to play at some point. If true, how much did they earn?

Were these expensive legal fees to luxury law firms a factor in the government’s doggedness to pursue a matter completely in conflict with the public and national interest? In addition to the strong and inexplicable urge to divert public and paid-up investor stakes in Sankofa – Gye Nyame to a private business?

What a shame!

Source : Citi Newsroom