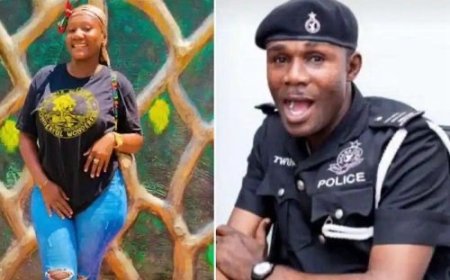

Alibaba co-founder Jack Ma implicated in intimidation campaign by Chinese regime

Billionaire appears to have been asked to pressure friend to return to China to help pursue out-of-favour official

The Chinese regime enlisted Jack Ma, the billionaire co-founder of Alibaba, in an intimidation campaign to press a businessman to help in the purge of a top official, documents seen by the Guardian suggest.

The businessman, who can be named only as “H” for fear of reprisals against his family still in China, faced a series of threats from the Chinese state, in an attempt to get him to return home from France, where he was living. They included a barrage of phone calls, the arrest of his sister, and the issuing of a red notice, an international alert, through Interpol.

The climax, in April 2021, was the call from Ma. “They said I’m the only one who can persuade you to return,” Ma said.

H, who had known Ma for many years, recorded the call. He had done the same for calls he had received from other friends, as well as Chinese security officials, who had called in the weeks before, all with the same message.

Transcripts of those calls presented in a French court, along with other legal records, provide a rare insight into some of the methods used by the Chinese regime to exert its influence around the world. The documents lay out in detail how a combination of threats, co-opted legal mechanisms and extrajudicial pressures are used to control even those beyond the country’s borders.

The findings are part of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’ (ICIJ) China Targets project, in which journalists documented the methods the Chinese regime uses to track and crush dissent abroad. The team includes the Guardian as well as Radio France and Le Monde, who obtained the transcripts and other legal paperwork.

A spokesperson for the Chinese embassy in the UK said: “The so-called ‘transnational repression’ by China is pure fabrication.”

Extradition threat

H, 48, a China-born citizen of Singapore, was in Bordeaux, France, when he received the call from Ma. A year earlier, a warrant had been issued by Chinese police for H’s arrest on charges of financial crime. Then, China had put out a notice for him through Interpol’s international criminal alert system. The French authorities confiscated his passport while they considered whether to extradite him.

The transcripts show that on the call, Ma suggested all of H’s problems would go away if he would help in the prosecution of Sun Lijun, a Chinese politician who had fallen out of favour with the ruling Chinese Communist party (CCP). Sun was being prosecuted for taking bribes and manipulating the stock market. “They are doing this all for Sun, not for you,” Ma said.

Sun, a former deputy security minister, was entrusted in 2017 with overseeing security in Hong Kong during mass protests against Beijing’s crackdown on democratic freedoms. He had been arrested the year before H started receiving the phone calls. Later, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) denounced Sun for “harbouring hugely inflated political ambitions” and “arbitrarily disagreeing with central policy guidelines”.

He became one of many top officials caught up in President Xi Jinping’s sweeping anti-corruption campaign, which human rights groups have said serves as a tool for Xi to purge his political rivals.

‘You have no other solution’

The transcript of the call suggests Ma was not happy to have been drawn into the affair. “Why did you involve me in this?” he asked H.

Like Sun, Ma had fallen out of favour with Xi’s regime. After giving a speech in October 2020 in which he criticised Chinese financial regulators, he was hit with repeated sanctions including a $2.8bn fine, and he disappeared from public view.

The phone call to H was made six months later. Ma explained in the call that he had been contacted by Chinese security officials. “They spoke to me very seriously,” Ma told H. “They say they guarantee that if you come back now, they will give you a chance to be exempted … You have no other solution … the noose will tighten more and more.”

Later, Ma called H’s lawyer to reiterate the message.

H did not return to China and his lawyers fought his extradition in the French courts.

Clara Gérard-Rodriguez, one of H’s lawyers, said: “We knew that if H went back to China, he would himself be arrested, detained, probably tortured until he agreed to testify … and that most of his assets, the shares of his company, would most likely be also transferred to other persons.”

The conviction rate for criminal cases in China is 99.98%, according to Safeguard Defenders, an organisation that investigates abuses by the Chinese regime. It has documented how forcible disappearances and torture are endemic within the justice system.

The money laundering charges brought against H in China, a year before the call from Ma, related to his connection to a credit platform, Tuandai.com. The founder of that company was jailed for 20 years for illegal fundraising. The Chinese police believed that he had attempted to hide some of the misappropriated funds when the investigation started. H, who had invested in the company, was accused of helping to move some of the money abroad through companies he controlled.

H’s lawyers told the French courts there was no evidence that he had known that the source of the funds was questionable. On a call to a friend, recorded in the French court documents, H protested his innocence. “None of this is true,” he said.

The Chinese government issued a red notice for H through Interpol, the international police watchdog. This flagged him as a potential criminal to police forces around the world and meant he was unable to travel. “It is like a pin through a butterfly,” said Ted R Bromund, an expert witness in legal cases involving Interpol procedures. “It holds someone down, locks them in place so they can’t get away.”

While red notices are used against serious criminals, campaigners have long warned that they can be abused. The British lawyer Rhys Davies recently told a government inquiry into transnational repression that red notices were “routinely used and abused by autocratic regimes to target dissidents and opponents overseas”. He called the system “the sniper rifle of autocrats because it is long-distance, targeted and very effective”.

While other countries, including Russia, Turkey and Rwanda, have also been known to abuse the system, China’s tactics are different, according to experts. Instead of relying on extraditions, the Chinese authorities use Interpol to locate people and then they ramp up the pressure, threatening them and family members back home until the individual agrees to return “voluntarily”.

A spokesperson for Interpol said the system meant thousands of the world’s “most serious criminals” were arrested every year. They added: “Interpol knows red notices are powerful tools for law enforcement cooperation and is fully aware of their potential impact on the individuals concerned, which is why we have robust – and continuously assessed and updated – processes for ensuring our systems are used appropriately.”

‘Psychological warfare’

As H waited in France, trapped by the legal process the red notice had begun, he received calls from friends and security officials, in what his lawyers called “all-out psychological warfare”. Sometimes the tone was friendly, with promises that all charges would be dropped; other times it was more threatening.

Transcripts of the call with the deputy investigator of the unit prosecuting Sun, Wei Fujie, suggest he promised H that if he returned there would be “no prosecution now, plus the cancellation of the red notice”.

A friend called and told H: “Within three days your whole family will be arrested!” Days later, H’s sister was arrested in China.

His case is far from unusual. The ICIJ’s China Targets project logged the details of 105 targets of transnational repression by China, in 23 countries. Half of them said their family members back home had been harassed through intimidation and interrogation by police or state security officials.

Rehabilitation

When H’s case came before the Bordeaux court of appeal, in July 2021, the court denied the extradition request. Later, the red notice was removed from Interpol’s systems. H’s lawyers successfully argued that the extradition request had been issued for political purposes, to compel testimony against Sun.

Sun was convicted of manipulating the stock market, taking bribes and other offences, without H’s intervention in the prosecution. He was given a suspended death sentence.

H, unable to trade or work in China, could not pay back loans or rent on a luxury property and became engulfed in debts totalling $135m, according to Chinese media. He declined to comment when approached by the Guardian.

A spokesperson for the Chinese embassy in the UK said: “China always respects the sovereignty of other countries and conducts law enforcement and judicial cooperation with other countries in accordance with the law.”

Representatives for Ma raised questions about his identity in the calls. The Guardian spoke to H’s lawyers, who said he had known the billionaire for many years prior to the call and that he had no doubt the caller was Ma. Throughout the legal process in which his lawyers challenged the red notice there were no questions raised about the identities of the callers.

Ma did not respond further to the Guardian.

Earlier this year, he was seen energetically applauding Xi at a meeting of business leaders in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People – a sign, according to local media, of the billionaire’s public rehabilitation.

Gérard-Rodriguez, H’s lawyer, said: “We saw and learned publicly of Jack Ma’s disappearance … this man, thought to be untouchable, extremely powerful, extremely well-connected in every country in the world, disappeared completely for several months and then reappeared, pledging his allegiance to the Chinese Communist party.

“And in the end, it was the same thing expected of H … that he would return to show his loyalty, to show which side he was on.”