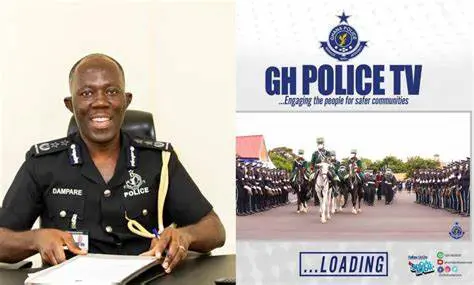

Does the Police law empower police to run a broadcasting service?

Police TV, Fire Service TV—and soon, perhaps Immigration TV, OSP TV, NACOC TV, or EOCO TV? Seriously?

While the stated intent may be to promote outreach or transparency, there are significant concerns about the potential misuse of such platforms to control narratives or erode media independence.

Each state institution is established to fulfil a specific mandate: law enforcement by the police, territorial sovereignty by the military, public broadcasting by the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation, and financial audits by the Audit Service, among others. What every institution must avoid is what I term mandate elasticity—stretching its functions into areas beyond its legal remit.

For instance, the police, with nearly 50,000 personnel, could argue that it is practical to run transport services. While offering limited transport for staff might be permissible, establishing a large-scale transport service—even for free—would constitute mandate elasticity. Transport is a regulated industry with designated agencies to oversee such operations. Similarly, running a TV station is not an ancillary service but part of a regulated broadcasting industry, which falls outside the primary responsibilities of law enforcement agencies.

Legal and Constitutional Concerns

Can law enforcement agencies run television stations? Several constitutional and legal questions arise:

- Mandate and Legal Basis

Does the Constitution or the Police Service Act authorise a law enforcement agency to operate a broadcasting service? If not, such ventures are extraneous to their core duties.

- Ownership and Oversight

If a station like Police TV is state-owned, the National Media Commission (NMC) is mandated under Article 168 of the 1992 Constitution to appoint its leadership in consultation with the President. Additionally, state-owned media must comply with Articles 55(11), 55(12), and 163, which require fair and equitable coverage for all, including political parties and protesters. Would Police TV offer such balanced representation?

- Regulation

Who regulates Police TV? If the police themselves are the primary enforcers of broadcasting regulations, this raises the critical issue of accountability. Who watches the watchman?

International Context

This trend appears to have originated in Russia, where the Ministry of Internal Affairs operates Police Wave TV for propaganda purposes. Similarly, the Nigerian Police Force launched Police TV to improve public communication, while Indian police departments in states like Tamil Nadu run TV channels for crime prevention and public education.

However, in most countries, law enforcement agencies do not own TV stations. Instead, they rely on public broadcasters, private media, and digital platforms to communicate with the public.

Why Most Democracies Avoid This

- Neutrality: In democracies like the UK and the US, law enforcement agencies must remain neutral to maintain public trust. Owning media could create perceptions of bias or propaganda.

- Press Freedom: Independent media are vital for holding law enforcement accountable. Agency-owned stations could undermine this by controlling narratives.

- Cost and Efficiency: Operating a TV station is expensive and diverts resources from critical law enforcement priorities. Social media, public service announcements, and partnerships with existing broadcasters offer cost-effective alternatives.

Balancing Education and Accountability

Law enforcement agencies have a clear mandate to educate the public on crime prevention. However, this should be done in collaboration with constitutionally mandated bodies like the National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE) and existing broadcasters, rather than through ownership of media platforms. Even the NCCE, which is tasked with public education, is not authorised to run a broadcasting service independently.

Conclusion

The venture into TV station ownership by law enforcement agencies raises constitutional, legal, and accountability concerns. While public education is essential, it must be done within the limits of the law and through existing media channels to preserve neutrality, press freedom, and financial prudence. In my considered opinion, this issue warrants urgent attention, even if it seems unlikely to feature prominently during the current political season. It is a matter of public interest that cannot be ignored.

Source: Sammy Darko

The writer is a lawyer and lecturer in media law and public interest journalism. He is currently an anti-corruption advocate.