Why Covid-19 seems to be becoming milder

Covid-19 is now ubiquitous – but hospitalisations seem to be on a downward trajectory. No one knows why.

When virologists took their first peek at XEC, the Covid-19 variant which started to become dominant in the autumn of 2024, the early signs were ominous.

The latest descendant of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, XEC had arisen through recombination, a process where two other variants had forged their genetic material together. Tests seemed to indicate that this would easily allow it to evade the immune protection offered by past infections or the latest iterations of the Covid-19 vaccines, based on the older JN.1 and KP.2 variants.

"The spike protein is quite different from previous variants, so it was quite easy to assume that XEC has the potential to evade immunity induced by JN.1 infection," says Kei Sato, a virology professor at the University of Tokyo, who carried out one of the first studies of XEC, published in December 2024.

In the US, infectious disease specialists braced themselves for an immediate surge in hospitalisations in the wake of the Thanksgiving holiday weekend. But it didn't happen. Surveillance testing carried out by measuring Covid in wastewater samples across major cities indicated that XEC was definitely infecting people. However, the numbers of people actually ending up in hospital was considerably less than previous winters. According to CDC data, the rate of hospitalisations at the start of Dec 2023 was 6.1 per 100,000 people. During the equivalent week in December 2024, that had fallen to two per 100,000 people.

What was going on?

"Right now, we're seeing pretty low levels of people who are critically ill, even though there's an astronomical amount of Covid in wastewater," says Peter Chin-Hong, a professor in the Health Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of California, San Francisco. "It just shows that regardless of how scary a variant might look in the lab, the environment in which it lands is much more inhospitable."

Some indications suggest that Covid in 2025 is a milder disease. The once common symptoms of loss of taste and smell are becoming less common. And though some people are being hospitalised and dying, Chin-Hong says the vast majority of people will either be asymptomatic or experience a cold so mild that some might well mistake it for a seasonal allergy, such as a pollen complaint. While immunocompromised individuals are still particularly vulnerable, he believes that the major risk factor for more severe Covid is now simply being over the age of 75.

Despite this, experts have advised that all vulnerable groups should get the latest Covid-19 vaccine, which can provide vital protection against serious illness, hospitalisation and death. And while XEC seems to cause less severe disease, there's no guarantee that more severe variants won't emerge in the future. This means the threat posed by Covid-19 is far from over and the virus should not be underestimated. Experts expect it to continue being a significant and persistent threat to public health. The risk of developing Long Covid has not gone away either. For some people, the condition can last years.

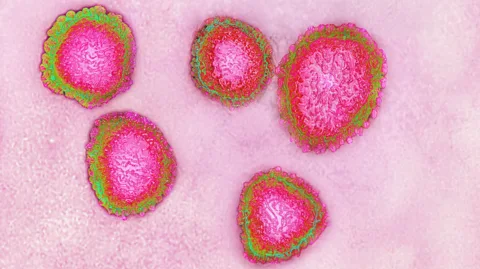

Like the coronaviruses that cause the common cold, some scientists have predicted that Covid-19 will evolve into a mild infection (Credit: Getty Images)

Like the coronaviruses that cause the common cold, some scientists have predicted that Covid-19 will evolve into a mild infection (Credit: Getty Images)At the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, microbiology associate professor Harm Van Backel is a co-leader of the Mount Sinai Pathogen Surveillance Program, which applies the latest genomics technologies to conduct real-time tracking of bacterial, viral and fungal infections within the Mount Sinai health system. Van Backel explains that the data shows that Covid is contributing relatively little to the caseload so far this winter, despite the emergence of XEC. "For the past six months, I'd say it's been relatively quiet," he says. "In comparison with other respiratory viruses, I would say that SARS-CoV-2 is maybe, at least in hospitalised cases, about 10% of the respiratory virus infection burden that we're seeing this season."

Even when patients are admitted to hospital, the treatment protocols have changed markedly in the last two to three years. Chin-Hong recalls that anticoagulants or blood thinning medications would immediately be administered to lower the chances of clotting, but this is now no longer considered necessary. While steroids such as dexamethasone are still used in certain severe cases, he says that these tend to be exceptions, with antivirals being the predominant treatment needed.

"I think Omicron and its subvariants have increasingly focused more on causing milder upper respiratory cold symptoms rather than pneumonia and some of the invasive manifestations we've seen in the past like cardiovascular disease and clotting," says Chin-Hong. "It means that when people come into hospital, they tend to be in and out in a shorter period of time."

So what's happening?

As part of his work tracking various respiratory viruses at the University of Missouri School of Medicine, the molecular virologist Marc Johnson uses all kinds of avenues to examine the levels of Covid currently circulating. Just like Chin-Hong, he can confirm that there is plenty of it around.

"We started doing air sampling at a lot of sites around the university, and it's pretty rare that we could pull out a sample from around the students and not detect Covid," he says. "We're still getting exposed all the time, but most infections are probably just getting blunted."

But it hasn't been easy to deduce why. Sato explains that one of the reasons that new Covid variants often seem far scarier than they actually are, is because their virulence is typically tested by injecting them into hamsters. "But of course hamsters have not been vaccinated," he says. "Hamsters are very similar to the humans of 2019. They have no specific anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunity, so the situation with the humans of 2025 is quite different."

Yet antibody levels, the most easily measured form of immunity, do not seem to be notably contributing to our ability to blunt the latest forms of Covid. Vaccination rates around the world are plummeting – by the end of Dec, CDC data showed that just 21.5% of US adults and 10.6% of children had received the 2024-2025 Covid vaccine – while when Sato and his team studied the XEC variant, it appeared to easily evade neutralising antibodies arising from infections against previous Omicron subvariants.

Chin-Hong says that there are two possibilities. One is that the vast majority of people have now been both vaccinated and infected so many times that their bodies have developed a powerful immune memory of what the virus now looks like, meaning that new infections are swiftly removed before they can penetrate deeper into the body. He believes that the progressively falling numbers of new long Covid cases is a further indication that this may be happening.

"Even if Covid gets in, right now it's going to be identified and kicked out of the body pretty efficiently," says Chin-Hong. "Most of the time, it's not lingering around long enough to cause serious disease, or chronic problems. With long Covid, one of the hypotheses is that the virus is triggering this aberrant immune response, but if it's not able to stick around as long anymore, there's less risk of that happening,” he says.

The second possibility is that Covid has now settled into a rut, which will see it become progressively milder until it ultimately becomes akin to the common cold. Chin-Hong says that this would make sense, particularly when we draw parallels with historical coronavirus outbreaks.

"People often look to influenza pandemics like the 1918 Spanish flu for clues as to what might happen with Covid, but coronaviruses may be inherently different from influenza, and so coronaviruses of the past may give better clues for the future," says Chin-Hong. "Overall, it seems that we may see less invasive disease and long Covid over time as population immunity improves, despite the continued evolution of the virus to create variants like XEC that look scary in the lab."

Covid could still take some twists and turns

So far, Omicron, which emerged in November 2021, remains the latest Covid "supervariant", following the previous Alpha and Delta variants. While dozens of subvariants have subsequently appeared in the last three years, none have pointed to a radically new change in Covid's trajectory.

However, Johnson says that if an immunocompromised individual was to now be infected with an older strain of Covid such as the Delta variant from 2020, it could lead to something radically different. He believes this could have a more drastic impact in terms of illness and hospitalisations as it would look completely foreign to our body.

"They aren't as prevalent as they once were, but we still occasionally detect some of these strains from the first year or two," says Johnson. "We know that there's people who have a Delta infection [a variant first identified in India in December 2020]. If one of those older strains broke out and started spreading more widely, people's immunity would be kind of confused because it would look so different from everything we've seen in the past three years."

Some researchers who study Covid-19 in wastewater believe that the virus will eventually evolve into a gastrointestinal infection (Credit: Getty Images)

Some researchers who study Covid-19 in wastewater believe that the virus will eventually evolve into a gastrointestinal infection (Credit: Getty Images)It's also plausible that something even stranger might unfold. According to Johnson, there are some early signs that Covid's eventual trajectory could lead it to become a faecal-oral virus, more akin to norovirus, cholera or hepatitis A than the common cold.

On the social media platform X, Johnson describes himself as a "wastewater detective", and he says that some of the most revealing predictions can be made from tracking Covid in the sewers. SARS-CoV-2 has been known to sometimes persist in the gut over the long term, and Johnson and his colleagues have identified various individuals who seem to have persistent gut infections. This has been possible because of Covid viruses with unusual patterns of RNA that have only been spotted in the sewer system – and not in samples from clinical settings such as hospitals. Each of these "cryptic lineages", as they are termed, are being repeatedly excreted by a particular anonymous individual.

Johnson's hunch is that this occasionally happens because a strain of Covid has acquired mutations which allow it to become a persistent gastrointestinal infection. As a result, he believes it is plausible that SARS-CoV-2 could eventually find a way of being spread via stool particles, just like other faecal-oral viruses.

"A lot of the bat coronaviruses, that's how they spread," says Johnson. "Interestingly, the evolutionary ancestors of Covid were not respiratory viruses, they were enteric viruses [those that live in the gut], spread via faecal-oral routes such as contaminated food, water or interpersonal contact. So it's possible that Covid could become an entirely food-borne pathogen, but that's probably not happening any time soon."

The other key question is the potential consequences of having a longer-term Covid gastrointestinal infection and how common this is. To try and find out more, Johnson is now attempting to recruit people who have experienced long-term gastrointestinal problems in the aftermath of an acute Covid infection, for a study.

Johnson believes it is particularly important for public health to try and understand some of the consequences of long-term Covid gut infections. He's noticed that after a period of time, sometimes many years, most of the cryptic lineages he spots repeatedly in wastewater ultimately disappear. "My guess is that the person dies, but I don't know that for sure or why," he says. "There's a lot of unanswered questions."

Because of this, while the vast majority of Covid infections appear to be benign, researchers like Johnson and Chin-Hong insist that it is still important for people to get vaccinated, and for companies to continue working to develop the next generation of vaccines. In addition to annual boosters, Chin-Hong says that the next phase of Covid vaccine development is mucosal vaccines which can actually prevent onward transmission of the virus, not just serious infections and illness. Work is also continuing towards a universal Covid vaccine which doesn't need to be updated on a yearly basis.

"At the end of the day, what happens next with Covid is still somewhat unpredictable," says Chin-Hong. "While there is still some risk of severe illness and hospitalisation, we still need better therapeutics and vaccines, for some people at least in the future."

--

Source: BBC