The trillion-dollar climate puzzle that's become a diplomatic nightmare

As countries negotiate a new global goal to raise climate cash, these five charts show why discussions are so fraught.

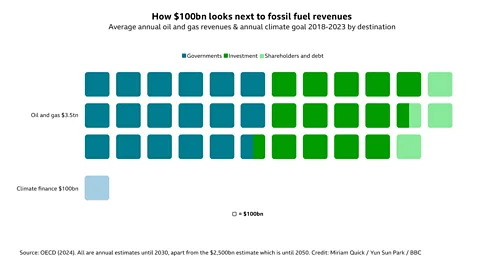

A hundred billion dollars. It's a staggering amount of money, although there are in fact now 16 individuals with personal assets worth more than this amount. But at the ongoing UN climate talks it's also a highly loaded figure, especially for countries on the frontlines of climate change.

It's the threshold amount that, back during turbulent negotiations in 2009, rich countries promised to "mobilise" each year by 2020 to help the billions of people in developing countries transition to a greener economy and cope with the impacts of climate change.

This may sound like a lot, but it is already considered too little. The new number that's being floated by many developing countries: at least a trillion.

Climate negotiators at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, are discussing the details of how much money rich countries should provide to poor countries to help them mitigate emissions and cope with climate impacts. What they haven't decided yet is how much it will be – or many of the other details, such as who will contribute what and is the target date to deliver the money. A huge range of options have been put forward by different groups and countries.

The question is ultimately one of justice, those countries say. Richer nations have, after all, historically caused the lion's share of climate change. Poorer nations not only have less means to make costly climate adaptations, but the problem of climate change was also largely not of their making.

As talks continue in Baku, here are five key charts to help put the fraught discussions into context – and show what is really at stake.

What's been paid so far?

Money is a tough topic that has caused a lot of tension at climate talks for decades now, even as climate costs around the world continue to rise.

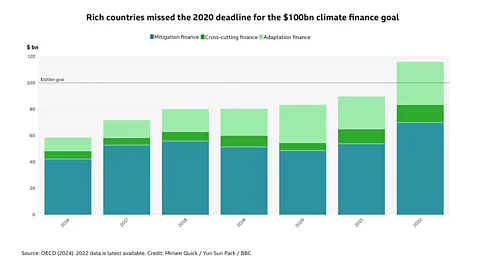

Rich countries failed to meet their promised 2020 deadline for the $100bn goal, only reaching the yearly goal for the first time two years later in 2022, as the chart below using figures from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) shows.

These countries have also been criticised for how they are delivering the money: for example, they are primarily providing money in the form of low-interest loans, that have be repaid, rather than grants, which don't. Countries have also reclassified existing development aid rather than contributing fresh funding, according to a report by the climate news site Carbon Brief. Analysis by other organisations and researchers say the amount transferred is actually far lower than the OECD figures, meaning the $100bn goal still hasn't been met.

Speaking at COP29, UN climate chief Antonio Guterres said "now more than ever" finance promises must be kept. "Developing countries eager to act [on climate change] are facing many obstacles: scant public finance; raging cost of capital; crushing climate disasters; and debt servicing that soaks up funds," he said. "We need a new finance goal that meets the moment."

If the new climate finance goal fails, we will all feel the impact, says Charlene Watson, senior research associate at Overseas Development Institute (ODI), a global think tank based in London, UK. "It [would be] a global failure. We are all not reaching the global 1.5C target." (Read more about why 1.5C is a critical threshold for the climate).

The focus on climate finance is coming now because back in 2015, countries at the COP21 talks in Paris agreed to set a new collective goal for it before 2025.

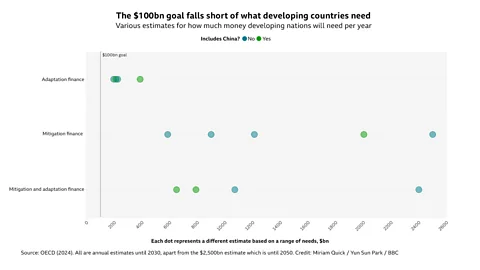

The $100bn goal, which was announced 15 years ago at a previous conference, COP15, is "now clearly out of sync with the total needs" of developing countries, says Joe Thwaites, senior advocate in international climate finance at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), a US non-profit.

The only conditions fully agreed so far for the new goal are that it will be "from a floor of $100bn per year" and "take into account the needs and priorities of developing countries".

The original $100bn goal, in contrast, was a political number, says Watson. "It wasn't a number that was based on developing country needs. The [new goal] is supposed to be based on those needs. And those needs are just tremendous."

What's actually needed?

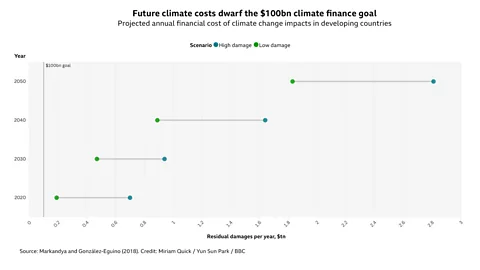

Residual damages are damages from climate change that cannot be prevented with adaptation measures (Credit: Miriam Quick/ Yun Sun Park/ BBC)

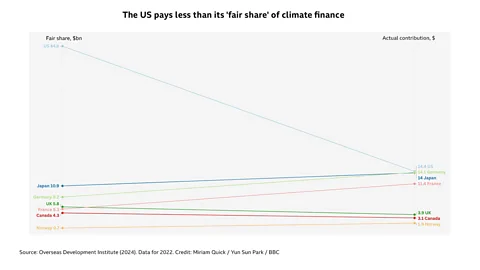

Residual damages are damages from climate change that cannot be prevented with adaptation measures (Credit: Miriam Quick/ Yun Sun Park/ BBC) The ODI calculated how much of the $100bn goal each developed country should pay to developing countries (Credit: Miriam Quick / Yun Sun Park/ BBC)

The ODI calculated how much of the $100bn goal each developed country should pay to developing countries (Credit: Miriam Quick / Yun Sun Park/ BBC)