Burning old TVs to survive: The toxic trade in electrical waste

You can see thick plumes of smoke rise from the Agbogbloshie dumpsite from miles away.

The air at the vast dump, in the west of Ghana’s capital Accra, is highly toxic. The closer you get, the harder it is to breathe and your vision starts to blur.

Around these fumes are dozens of men, who wait for tractors to unload piles of cables before setting them on fire. Others climb up a toxic waste hill and bring down TVs, computers and washing machine parts and set them alight.

The men are extracting valuable metals like copper and gold from electrical and electronic waste - or e-waste – much of which has made its way to Ghana from rich countries.

“I don’t feel well,” says young worker Abdulla Yakubu, whose eyes are red and watery as he burns cables and plastic.

“The air, as you can see, is very polluted and I have to work here every day, so it definitely affects our health.”

Abiba Alhassan, a mother of four, works near the burning site sorting out used plastic bottles, and the toxic smoke does not spare her either.

“Sometimes, it’s very difficult to breathe even, my chest becomes heavy and I feel very unwell,” she says.

E-waste is the world's fastest-growing waste stream, with 62 million tonnes generated in 2022, up 82% from 2010, according to a UN report.

It is electronisation of our societies that is primarily behind the e-waste rise — ranging from smartphones, computers and smart alarms, to automobiles with electronic devices installed, whose demand is steadily on the rise.

Annual smartphone shipments, for instance, have more than doubled since 2010, hitting 1.2 billion in 2023, according to a UN Trade and Development report this year.

Most frequently seized item

The UN says only around 15% of the world’s e-waste is recycled, so unscrupulous companies are seeking to offload it elsewhere, often through middle men who then traffick the waste out of the country.

Such waste is difficult to recycle because of their complex composition including toxic chemicals, metals, plastics and elements that cannot be easily separated and recycled.

Even developed countries do not have adequate e-waste management infrastructure.

UN investigators say they are seeing a significant rise in the trafficking of e-waste from developed countries and rapidly emerging economies. E-waste is now the most frequently seized item, accounting for one in six of all types of waste seizures globally, the World Customs Organisation has found.

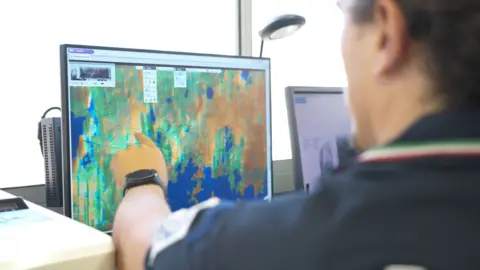

Officials at Italy’s Naples port showed the BBC World Service how traffickers mis-declared and hid e-waste, which they said made up around 30% of their seizures.

They showed a scan of a container bound for Africa, carrying a car. But when port officials opened the container, broken parts of vehicles and e-waste were stacked inside, with oil leaking from some of them.

“You don’t pack your personal goods like this, much of it is meant for dumping,” says Luigi Garruto, an investigator with the European Anti-Fraud Office (Olaf), who collaborates with port officials across Europe.

Sophisticated trafficking tactics

In the UK, officials say they are also seeing a rise in trafficked e-waste.

At the Port of Felixstowe, Ben Ryder, a spokesman for the UK Environment Agency, said waste items were often wrongly declared as reusable but in reality, “broken down for precious metals and then illegally burnt after they reach the destination” in countries like Ghana.

Traffickers also attempt to conceal e-waste by grinding it down and blending it with other forms of plastic that can be exported with the correct paperwork, he said.

A previous report by the World Customs Organization showed there had been an increase of almost 700% in trafficking of end-of-life motor vehicles - a huge source of e-waste.

But experts say such seizures and reported cases are just the tip of the iceberg.

Although there has been no comprehensive global study that traces all the e-waste trafficked out of the developed world, the UN e-waste report shows countries in Southeast Asia still remain a major destination.

But with some of those countries now clamping down on waste trafficking, UN investigators and campaigners say more e-waste is making its way to African countries.

In Malaysia, officials seized 106 containers of hazardous e-waste from May to June 2024, according to Masood Karimipour, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime's regional representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

But traffickers often outsmart authorities with new smuggling tactics and governments don’t catch up fast enough, UN investigators say.

“When ships carrying hazardous waste like e-waste cannot easily offload them in their usual destination, they turn their beacon off when they are in the middle of the sea so that they cannot be detected,” said Mr. Karimapour.

“And the illegal shipment is dumped at sea as part of a business model of organised crime activity.

“There are far too many groups and far too many countries profiting from this global criminal enterprise.”

Chemicals of high concern

When e-waste is burnt or dumped, the plastic and metals it contains can be very hazardous to human health and have negative effects on the environment, a recent report by the World Health Organisation (WHO) said.

The WHO says many recipient countries also see informal e-waste recycling - meaning untrained people including women and children are doing the job without protective equipment and the right infrastructure, and are being exposed to toxic substances like lead.

The International Labour Organisation and WHO estimate that millions of women and child labourers working in the informal recycling sector may be affected.

The organisations also say exposure during foetal development and in children can cause neurodevelopmental and neurobehavioural related disorders.

From January 2025, global waste treaty the Basel Convention will require exporters to declare all e-waste and obtain permission from recipient countries. Investigators are hopeful that this will close some of the loopholes that traffickers have been using to ship such waste across the world.

But there are some countries including the US — a major e-waste exporter — that have not ratified the Basel Convention - one reason campaigners say e-waste trafficking continues.

“As we start to crack down, the US is now more and more shipping trucks across the border to Mexico,” said Jim Puckett, executive director of Basel Action Network, an organisation campaigning to end toxic trade including e-waste.

Back at the Agbogbloshie scrapyard in Ghana, the situation is getting worse by the day.

Abiba says she spends almost half the money she earns from collecting waste on medicines to deal with conditions resulting from working at the dump.

“But I am still here because this is my means of survival and that of my family.”

The Ghana Revenue Authority and Environment Ministry did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Source: BBC