The 24-hour economy revisited – Nii Moi Thompson writes

Nearly a year ago, former president John Dramani Mahama set the otherwise dull pre-campaign season agog with his promise to transform Ghana’s development fortunes with a 24-hour economy (24-HE) in his possible second term.

Almost immediately, some critics dismissed the strategy as impractical, arguing that Ghana’s economy was too small to absorb any increase in output from 24-hour business operations.

Mr Mahama quieted them with the disclosure that he would chair a special inter-sectoral team to accelerate exports and open up foreign markets for Ghanaian businesses.

The critics then regrouped under the banner that Ghana already had a 24-hour economy, including some light-manufacturing firms, mining companies, pharmacies and hospitals, the police service, other government services, and chop bars (although the last is a rarity, even in big cities). Others argued that it is impossible to get all businesses to operate 24 hours.

This, however, was a distortion of the strategy, originally proposed in Mr. Mahama’s 40-year National Development Plan. It’s about more than the handful of companies that currently operate around the clock, by default, not strategy. The 24HE, by contrast, is a purposeful strategy to utilise as much idle productive capacity as possible while strengthening existing but under-utilised capacity across all businesses, irrespective of when they operate. Under the strategy, the majority of businesses, particularly SMEs, will continue to operate during the day.

They will receive special support to operate more efficiently, expand their operations, and create more jobs, resulting in higher profits, better wages, an expanded tax base, and more government revenue to finance development.

As of 2023, SMEs accounted for just over 90% of businesses in Ghana, about 80% of employment, and 40-50% of GDP, similar to their global averages. As with their counterparts elsewhere, including advanced economies, Ghana’s SMEs tend to have lower productivity (efficiency) than their bigger cousins do.

Under the 24HE, this deficiency will be addressed through an accelerated programme to boost SMEs’ productivity under a revitalised Local Economic Development (LED) programme, which will include a continuation of Mr Mahama’s Markets Modernisation Programme and a wider modernisation of the informal economy.

A Business Climate Survey (BCS) to guide wider policies for private sector development will also be introduced.

The minority of businesses that are expected to operate 24/7 at the upper end of the strategy will be “frontier firms,” which are, ideally, bigger and capable of investing and operating on a large scale and employing more people than a typical SME would.

They also tend to have world-class management systems and are quick to adopt technology and promote innovation. They account for a disproportionately bigger share of exports and government revenue and have the capacity to nurture SMEs and source materials from them for their operations. As a result, even though they may make up not more than 5% of all enterprises, these frontier firms will play a dynamic and outsized role in the 24HE, promoting both backward and forward linkages, a major source of jobs.

It must be noted that “productivity” is not the same as “production” (output), so while extending the number of hours a firm operates may increase its total production, it can only improve productivity by efficiently utilising all its productive assets, including labour, facilities, equipment, and time. Output per worker/per hour worked (as productivity is technically measured) must therefore rise, or the inefficiencies will ultimately collapse the company, even if production is rising.

The government, too, must improve its productivity through comprehensive public sector reforms at the national and local levels. A distinction must also be made between productive activities, such as manufacturing, and support services, such as port services or public safety, for purposes of effective policy-making.

The modernisation of agriculture and agro-processing forms another key feature of the 24HE. The entire value chain will be strengthened to boost food production through improved productivity (efficiency) and to supply the industrial sector with critical inputs, similar to Gen. Acheampong’s Operation Support Your Industry programme.

From talk to action.

Implementing the 24HE strategy will not be as easy as it appears in writing, especially given the deep economic crisis currently facing the country. For example, investment in productive assets, such as factories, equipment, and infrastructure, is a precondition for economic growth. Yet, as shown in the graph below, such investment (as a share of GDP) has declined from a decade-high of 27.0% in 2015 to its lowest of 10.7% in 2023, according to the Ghana Statistical Service. Reversing this plunge will require a surge in investment, particularly, foreign direct investment, on an unprecedented scale.

Other critical inaugural initiatives would be:

- A legislative and policy agenda to set the parameters for the 24HE

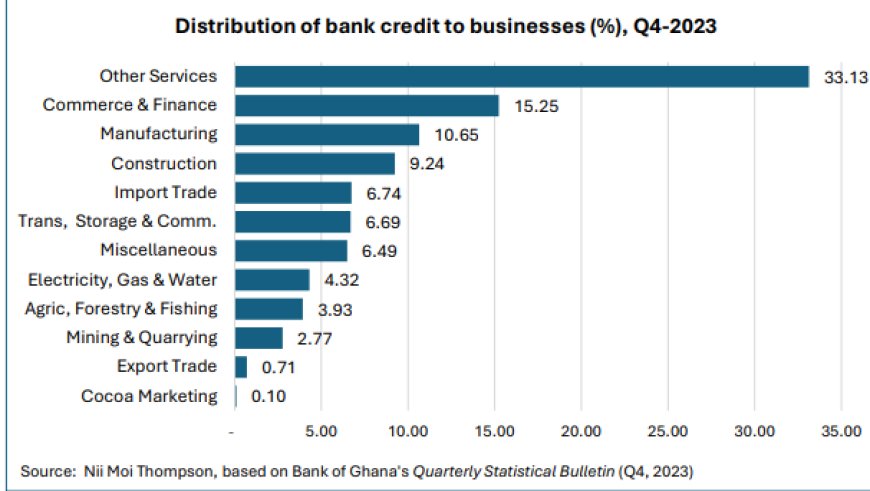

- A drastic overhaul of fiscal and monetary policies to re-orient them towards employment-intensive growth, especially exports, which currently receive less than 1.0% of credit from banks, compared to nearly 7.0% for imports and 15.0% for “commerce and finance,” the largest.

- Emergency public sector reforms, with a particular focus on SOEs, such as ECG, Ghana Water Company, and various infrastructure ministries, departments, and agencies.

- Accelerated TVET training in preparation for a surge in infrastructure development.

- Restructuring of Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) to drive Ghana’s scientific and industrial revolution.

- Mobilisation of public support for the strategy.

Writer| Nii Moi Thompson

The author was the DG of the National Development Planning Commission and the author of the analysis for the 24HE for the Commission’s 40-Year National Development Plan.