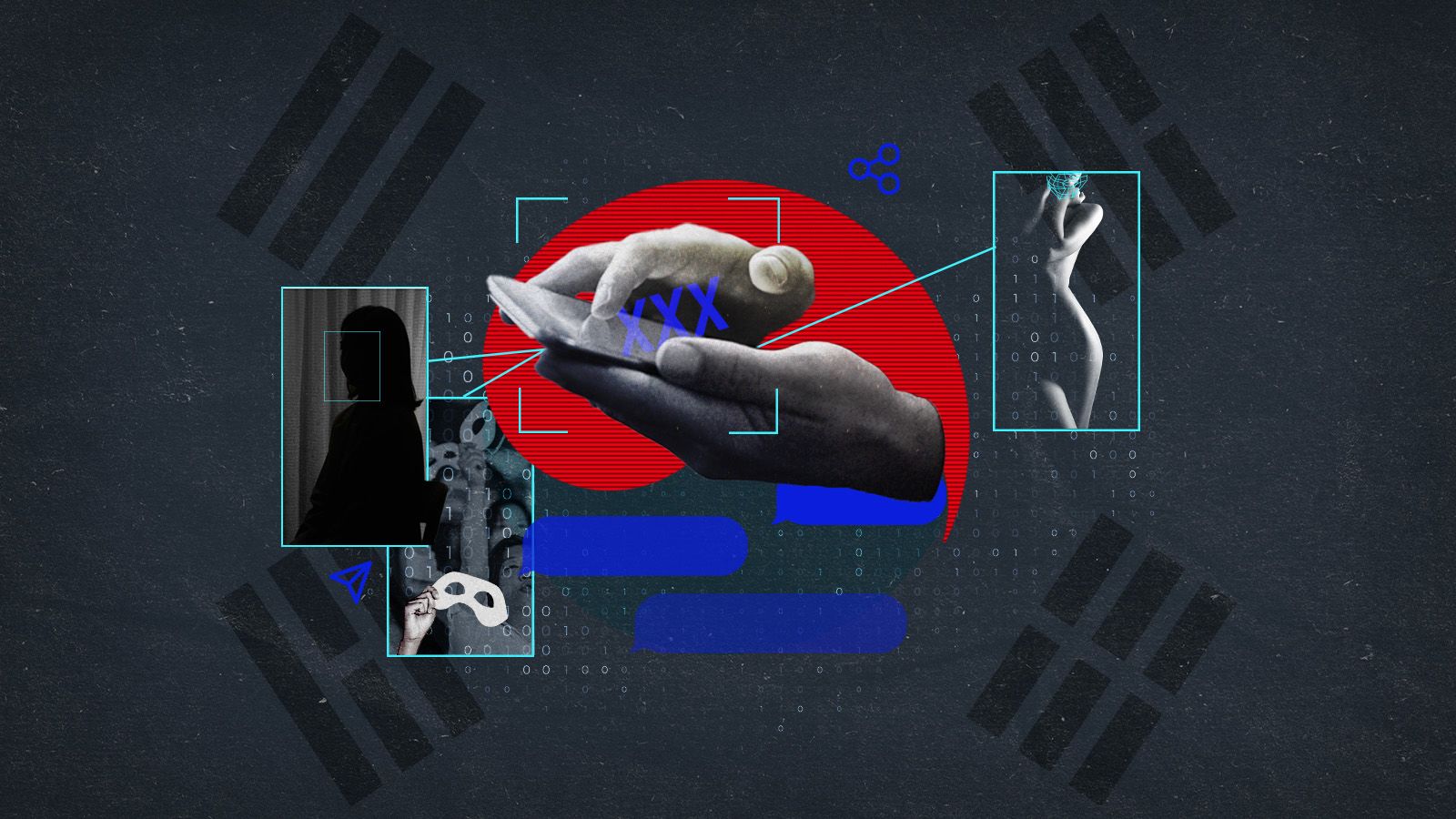

SCAM : Inside Asia's Criminal Network

Warning: this story contains distressing details and images

"I was taught how to hit on them for about three or four days. After being friends for about a week, you go in for the 'kill'."

Poom-Jai*, 17, is talking about his job. Over several months, the Thai teenager was trained to lure, befriend and defraud lonely people online, with brutal efficiency.

"I wondered when I scammed them, would they become penniless, would they face hardship."

Based in highly secretive, heavily guarded compounds, fraud factories - similar to the ones Poom-Jai worked in - are spread across South East Asia, where the online scam industry has exploded.

Within them are thousands of workers, who are taught to steal the hearts and money of millions of victims worldwide. Increasing numbers of Brits and Americans are falling prey to their scams which range from fake romances to online gambling.

The scammers' money, names and digital footprints are often buried behind opaque money laundering schemes.

For the first time, Sky News has gone undercover inside one of these scam centres in Cambodia, exposing the reality of life inside for the thousands of workers like Poom-Jai, who find themselves caught in a criminal web they can't escape from.

Videos have emerged from inside scam compounds allegedly showing workers being tortured.

THE PIG BUTCHER

The scam Poom-Jai carried out was called "pig butchering". Victims or "pigs" are persuaded to invest money into fraudulent schemes until they're "fat" enough to "slaughter".

Translated - that means you wait until they've given you all the money they can... then you steal it.

Scammers are taught to build trust but everything they say is fake. They give fake names, build fake profiles and tell fake stories.

"They fall in love with me," Poom-Jai says of his victims, looking almost detached as he describes the process. Sometimes, he would send videos of people masturbating pretending it was him and encourage his victims to share real explicit videos of themselves.

"They fall in love with me," Poom-Jai says of his victims, looking almost detached as he describes the process. Sometimes, he would send videos of people masturbating pretending it was him and encourage his victims to share real explicit videos of themselves.

It was all part of a well-rehearsed script delivered by an army of workers waiting to see who would take the bait.

But Poom-Jai isn't the villain of this story. Like many of those working in scam centres, he is also a victim.

He travelled to Cambodia, leaving behind his family and friends, after a romance scammer promised him an administrative role with a big salary.

But instead he found himself with no choice but to start scamming.

Like so many others, lured into these jobs under false pretences and then intimidated with violent threats, once Poom-Jai arrived his life revolved around the scam centre - working, eating and sleeping there, often unable to leave without permission.

Moved around between compounds, Poom-Jai became so desperate that he nearly died in an attempt to escape.

'THEY BROUGHT AN ELECTRIC BATON'

Many scam centres in Bavet and across the region are run by Chinese mafia but the workers come from all over the world.

Some join the scams willingly, desperate to make money. Others are trafficked, trapped into cyber slavery and tortured for failing to meet targets.

According to a recent report by the United States Institute of Peace, there are an estimated total of more than 300,000 scammers in Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos that account for at least £34bn in stolen funds worldwide.

The final compound Poom-Jai worked in was in Bavet. There, he was accused of stealing by his bosses.

"They kicked and punched me. I told them I didn't do it. Then, they brought in an electric baton."

Days later, he made a bid for freedom, removing the iron railings from a window and jumping from the eighth floor to another building.

After falling sharply, he severely twisted his leg and ended up in hospital. It was only thanks to the doctor who helped hide him from his criminal bosses that he survived and made it home to Thailand.

At the end of a dusty road, we found the imposing building where he says he worked. But the staff didn't want to talk.

THE RESCUER

"This is the worst human trafficking event in history," says Judah Tana, an Australian-born rescuer, talking about the horror associated with the scam industry.

Judah heads up Global Advance Projects, a charity that has helped about 700 people escape scam centres.

Based on the Thai-Myanmar border, Judah's phone never stops ringing. He is busy conducting delicate negotiations with victims, embassies and the militias who control the territory.

Judah Tana speaks to Sky's Cordelia Lynch on the Thai-Myanmar border

As he drives me along a winding road by the river, he shows me these huge scam centres glowing with bright lights along the border.

Getting anyone out of a compound is hard. In a country wrestling with civil war, it is hugely complex.

There's a new scam centre on the border, known as Taichang or Mountain View. Built 18 months ago, it is described as "hell on earth" by those who have escaped from it.

Judah's small team has already handled about 100 cases from there, he tells us. And if you can't pay an £8,000 ransom, "you're effectively stuck in there forever".

According to Judah, video and testimony from Taichang proves torture is common. He describes workers being hung with their arms above their heads for days at a time in so-called "dark rooms", tasered and denied food.

THE BURMESE BOOM TOWN

Some well-known scam farms, such as KK Park in eastern Myanmar, have reportedly started to improve after coming under international pressure. But workers still need to pay to get out of the prison-like compound and scamming is still rife.

As part of our investigation, I was invited into Yatai New City, a place that until recently was largely cut off to journalists. Just a few years ago, it was a quiet, rural town.

Now, it's bustling with business and has become a mini-Macau (the only place in China where casino gambling is legal) fuelled by billions of dollars in Chinese investment. It's also been linked to the growing online scams industry.

But today, Yatai has agreed to let us in. It appears they want to show us it's a normal place with nothing to hide. As soon as you arrive, you're greeted by a large rampart. Beyond the wall, it feels more like China in parts, than Myanmar.

The streets are thronging with people. But there are also lots of imposing, ominous buildings that look strikingly like the compounds in Cambodia. Signs warning against the use of forced labour dot the streets.

Much of the city's development was funded by a firm called Yatai International Holdings Group, which has gambling investments throughout South East Asia including Cambodia, the Philippines and Myanmar.

The chairman of the Myanmar branch, He Yingxiong, wants to talk. He's 35 years old, with a calm yet focused manner.

Yatai's founder, She Zhijiang, who's in jail in Thailand and wanted in China over alleged illegal gambling operations, has been "smeared" and "wrongly accused", insists He.

Yatai the company, he claims, neither supports nor allows human trafficking or scam centres. But there's a key caveat too - if they are here, it's not their responsibility. Yatai is just the "city developer" - what companies do is not really their business, he adds, repeating this line with a politician's persistence.

THE SCAM MASTERS

Back in Cambodia, to my surprise, a potential new way into the compounds materialises. After talking to recruiters in Bavet on the encrypted messaging app Telegram, my producer Rachael and I go armed with secret cameras to meet two women, claiming to be recruiters, at a coffee shop.

As soon as they sit down, they start describing how romance scams work. They say Bangladeshi people are the easiest to dupe into investing. We can make $800 a month with bonuses, they say, if we take a job with them.

The police, they insist, don't come near the compounds because the casinos that sit in front of them pay them off

That night, they arrange for us to do a job interview. We're asked to meet someone behind a casino. A car picks us up and drives us to a gated compound. It's a daunting drive.

I know once we are inside the only way out is with an escort and we could be rumbled at any point. As we drive in, I'm struck by how it looks almost like a university campus with sports courts and restaurants.

We are led upstairs into a big room where we are asked to sit down with the man they call the Boss, the head of HR and two other employees. They get straight to the point.

"Firstly, you will have to know what we are doing here. It's scamming jobs. It's a fraud industry."

The US market is their big current target, she says, because of the number of wealthy people who can be manipulated online. The job being offered is "24/7".

Opposite us sits the man they call "master", who will teach us how to win people over. If we can win over easy targets like divorcees we could make $4m, we are told.

The woman doing most of the talking is affable and articulate. It's easy to see how she could get strangers to part with their savings. Most people are speaking Mandarin but we are told that AI can be used to translate scripts.

Then we get a tour of the accommodation, which is rooms full of bunk beds. There is music blaring and food served in the corridor. But while it might look similar to basic student accommodation, the difference here is you need to get permission to leave.

The last stop is one of the highly secretive scam rooms. After months of pouring over snatched video on social media, suddenly, I can see it with my own eyes.

It is well organised with rows and rows of people. Some are Vietnamese. Some Bangladeshi. Most are Chinese, they say. Many have multiple phones and are conducting multiple conversations with victims online.

"Those are marketing. Those are the killers," our guide tells us, pointing to rows of workers feverishly typing away.

THE BEREAVED

For some, the job can be fatal. In Thailand, Chatphisit Jitprasert says his brother, Thapakorn, died after falling from a compound in Poipet. "He was murdered, for sure," Chatphisit says, tearfully.

It's a murky, violent world where truth and justice remain elusive, but Chatphisit wants his brother's death to be a warning to all Thai people. "Don’t go there."

But people still are and the industry is growing rapidly. Beijing has started to clampdown on some of the worst offenders, taking aim at those trafficking Chinese victims and scamming Chinese nationals.

Cambodia has conducted some high profile raids on scam centres too, but there are question marks over the government's commitment to tackling the problem. The tentacles of this industry spread so far across borders that it will require a huge co-ordinated effort to bring about any real change.

We reached out to those responsible for the compounds featured in this article. We also contacted the Cambodian government. None of them responded to our requests for comment.

*Name has been changed

Source: Sky News